When pirate William Fly ascended the scaffold on July 12, 1726, his execution speech was a shock to its respectable recorder, attending minister Cotton Mather, as well as to the rest of the crowd assembled to see the spectacle of a pirate's hanging.

|

| Engraving of a pirate on the scaffold |

You see, the tradition of execution speeches was specific and long-established, although this genre has since fallen out of fashion (giving way to deathbed monologues followed by unexpected last-will-and-testaments), and William Fly's defiance of tradition was both bold and pointed. Execution speeches are supposed to show due penitence for the crime committed (or allegedly committed) by the condemned, and exhort the watching crowd not to follow in his or her bad example, concluding with a request for God's forgiveness; an acceptable variant is the assertion of innocence followed by a pious acknowledgement of one's sins in general.

Here are some examples:

"...And now I entreat you all to join with me in prayer, that the great God of Heaven, whom I have grievously offended, being a man full of all vanity, and having lived a sinful life, in all sinful callings, having been a soldier, a captain, a sea captain, and a courtier, which are all places of wickedness and vice; that God, I say, would forgive me, cast away my sins from me, and receive me into everlasting life. So I take my leave of you all, making my peace with God."

|

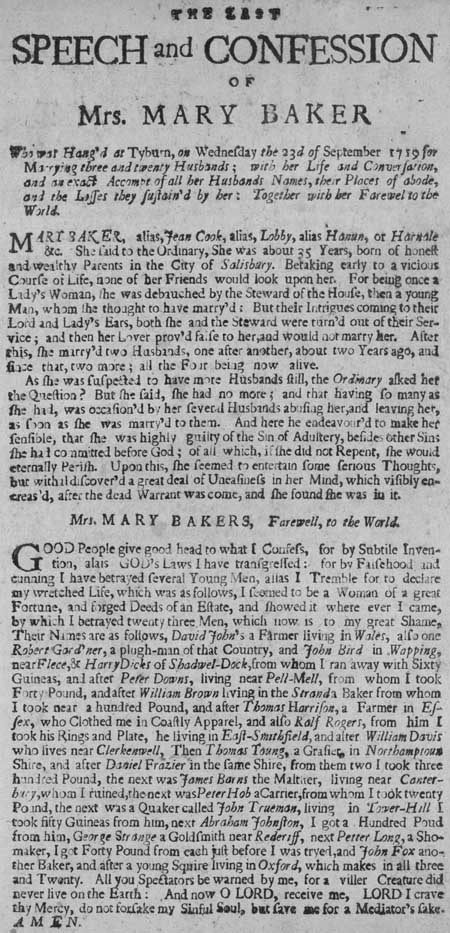

| Broadsides recounting executions and other sensational events were popular in the 18th century. |

"GOOD People give good head to what I Confess, for by Subtile Inven-

tion, alas GOD's Laws I have transgressed: for by Falsehood and

cunning I have betrayed several Young Man, alas I Tremble for to declare

my wretched Life, which was as follows, I seemed to be a Woman of a great

Fortune, and forged Deeds of an Estate, and showed it where ever I came,

by which I betrayed twenty three Men, which now is to my great Shame...

All you Spectators be warned by me, for a viler Creature did

never live on the Earth: And now O LORD, receive me, LORD I crave

thy Mercy, do not forsake my Sinful Soul, but save me for a Mediator's sake. AMEN."

When I that practice took

Of perpetrating piracy

For filthy gain did look.

To wickedness we all were bent,

Our lusts for to fulfil;

To rob at sea was our intent,

And perpetrate all ill.

I pray the Lord preserve you all

And keep you from this end;

O let Fitz-Gerald’s great downfall

Unto your welfare tend.

I to the Lord my soul bequeath,

Accept whereof I pray;

My body to the earth beneath:

Dear friend, adieu for aye."

William Fly, however, had no taste for mawkish poetry, and bucked tradition right from the start. Upon ascending the scaffold, he coolly inspected the noose he would hang from, and then "turned to the hangman in disappointment, and reproached him 'for not understanding his Trade.' But Fly, a sailor who knew the art of tying knots, took mercy on the novice. He offered to teach him how to tie a proper noose. Then Fly, 'with his own Hands [,] rectified Matters, to render all things more Convenient and Effectual,' retying the knot himself as the multitude who had gathered around the gallows looked on in astonishment. He informed the hangman and the crowd that 'he was not afraid to die,' that 'he had wronged no Man.' Mather explained that he was determined to die 'a brave fellow.' "

Then William Fly proceeded in this unconventional vein: He "did not ask for forgiveness, did not praise the authorities, and did not affirm the values of Christianity, as he was supposed to do, but he did issue a warning. Addressing the port-city crowd thick with ship captains and sailors, he proclaimed his final, fondest wish: that 'all Masters of Vessels might take Warning at the Fate of the Captain (meaning Captain Green) whom he had murder'd, and to pay Sailors their Wages when due, and to treat them better; saying, that their Barbarity to them made so many turn Pyrates.' Fly thus used his last breath to protest the conditions of work at sea, what he called 'Bad Usage.'" Quite the way to make a statement!

(This riveting account of William Fly's hanging is borrowed from Marcus Redeker's chronicle Villains of All Nations: Atlantic Pirates in the Golden Age - a thrilling read, and highly recommended.)

If any of my readers are ever so unfortunate as to find themselves upon the scaffold, they may or may not wish to be "launched into eternity with the brash threat of mutiny upon [their] lips" as was the bold pirate Fly; but this account will, I hope, give them the inspiration necessary to come up with a memorable last speech. After all, how can you break the rules without first knowing the rules?

I hope these guidelines will prove useful but not be too often needed, and I remain

Yours etc.